Numeric et Sustainability 🇬🇧

Presentation of the ideas I am developing in my research project on the study of the sustainability (or unsustainability) of ubiquitous artificial intelligence.

It proposes a model inspired by the scientific literature of the “Social Ecology” community, suggesting a study model based on the life of a biological organism and combining it with socio-economic aspects. In the proposed model, I consider the socio-technical aspects of AI in the form of three interacting blocks: flows, infrastructures, and needs. I intend to detail this model using tools commonly employed by the Information Systems community as well as other approaches, in a spirit of multidisciplinary openness. The expected contributions are a modeling of the metabolism of ubiquitous AI in contemporary society, the study of its limits through the prism of a finite planet, and possible pathways for shifting from the dominant model to a sustainable one, if such a model can exist. This work builds on my previous research conducted at the CRI on the principles and techniques of decentralization and self-sovereignty made possible by blockchain1, as well as my current research axes dealing with trust in information systems2 and experiments on lightweight embedded AI as a substitute for centralized models. The aim here is to provide tools for a critical reflection on AI, its promises and its limits, by combining contributions from digital sciences with those from systemic and socio-ecological approaches.

Motivations for Social Metabolism and Application to AI

The chosen approach builds on a vast body of research from social metabolism, defined as “Social metabolism encompasses the biophysical flows exchanged between societies and their natural environment, as well as the flows within and between social systems.” [Haberl et al. 2019].

This scientific approach draws inspiration from the communities of Urban Metabolism, Ecological Economics, Energy and Material Flow Analysis, as well as methods such as Life-Cycle Assessment and Integrated Assessment Models.

It relies on the triptych (nexus) stock-flow-services3, originally representing the stock of matter, material flows, and the societal services enabled by them.

One of the major contributions of social metabolism is the identification of several systemic phenomena:

- lock-in phenomena (lock-in or legacies) between these three components,

- leakage, when the adoption of a new artifact leads to an increase in the consumption of another,

- and the rebound effect, when the adoption of a supposedly more efficient service actually increases its environmental footprint due to the growth of its use.

I chose to apply this conceptual framework to the analysis of AI for three reasons:

- On the one hand, the rise of this technology tends to make its use pervasive in society, to the extent that many new “opportunities” for AI applications are emerging across all industrial sectors and in most households (at least in the Global North), with a risk of increasing technological dependency.

- On the other hand, its technological foundations present a very significant environmental footprint4.

- Finally, the large-scale deployment of the data centers required for AI infrastructure has a strong territorial impact and raises numerous issues of competition for resources [Lopez and Diguet 2023].

Although much research considers AI to be beneficial in certain areas — notably for reducing GHG emissions [SaberiKamarposhti et al. 2024] [Adegbite et al. 2024] — studies addressing the systemic effects of AI remain rare and limited to (albeit important) considerations of AI ethics [Stahl et al. 2023].

I aim to better understand the systemic impacts of AI deployment, to study the sustainability of the ubiquitous AI model, and to propose pathways for shifting toward sustainable alternatives. In this document, I begin by providing an illustrative example of a simplistic metabolic study focusing on a transport infrastructure (Section ). The objective of this example is to guide the reader in understanding the FIN model (Section ). I then proceed by explaining how the applied model can allow us to reason about the stability of a system (Section ) while taking into account its characteristics and first-, second-, and third-order effects. I continue by applying the model to the study of the metabolism of AI (Sections , , ) and justify the novelty of this approach. Finally, I propose directions for my future research within this theoretical framework (Section ).

Illustrative Example of a Socio-Metabolic Study

I begin this presentation by describing a simplistic metabolic model, purely for illustrative purposes, concerning the evolution of public transport in the city of Bordeaux during the 20th century.

Context

In 1900, the mayor of Bordeaux, Mr. Cousteau, inaugurated the first electric tram in Bordeaux, replacing the old horse-drawn models. At its peak in 1946, the network reached 253 km, 40 lines, and a total of 160,000,000 passengers per year (equivalent to 400 passengers per inhabitant per year). Mr. Chaban-Delmas, mayor from 1947 to 1995, decided as early as 1948 to completely dismantle the tram network and replace it with a fleet of buses. One of the reasons for this choice was the constraint posed by the dedicated tram tracks on individual automobile traffic. In 1997, facing road congestion in the city and the failure of the metro project, Mr. Juppé, the newly elected mayor, together with the Bordeaux urban community, decided to relaunch a tram project. Construction lasted 3 years for the initial delivery, and by 2023 the network reached 68,000,000 passengers per year (equivalent to 83 passengers per inhabitant per year)5.

It should be noted that the example of Bordeaux is not an isolated phenomenon, but one of many cases [Turnheim 2023].

FIN Model Applied to the Dismantling of the Tram in Bordeaux

The figure shows the interaction between the 3 components of our model: flows, infrastructures, and needs.

- Flows6 are the material or immaterial components that enter and exit our system with a short lifespan (arbitrarily taken as < 1 year) and are measured over a given period.

- Infrastructures7 are the material or immaterial components with a longer lifespan, which remain in the system for a certain time.

- Needs8 are what drive individuals to act within our system, through the means provided to them by the infrastructure in the form of need satisfiers according to [Max-Neef et al. 1991]. In first order, flows are used to build infrastructures, and infrastructures are created to meet needs.

There are also other relationships between the components of the model, of second order: infrastructure is not neutral with respect to either flows or needs. The deployment of infrastructure calls for an increase in the flow9 necessary to maintain it. The increase in available infrastructure also calls for the provision of new means to satisfy needs10.

Other third-order effects also appear. Individual benefits are tempered by negative externalities. In our example: not only does the increase in the need for individual car travel raise pollutant emissions, but it also reconfigures urban space by enabling the development of suburbanization as well as large-scale commercial areas on the outskirts, accessible mainly by car. It should be noted that the increase in the quantity of infrastructure and flows encounters the transgression of planetary boundaries, making the system ultimately unsustainable.

The difficulty of the situation lies in the lock-in between, on the one hand, flows and infrastructures and, on the other, between infrastructures and needs:

- The construction of infrastructure is capital-intensive and requires the amortization of investments over the long term. In this context, it is difficult to reverse infrastructure development decisions, and the tendency is to wait for full amortization before proceeding with dismantling11.

- Moreover, the gradual adaptation of the means of fulfilling needs through infrastructures creates a form of dependency. This dependency makes it more difficult to accept any profound modification of these infrastructures12. Lock-in contributes to the stability of the system, creating forces that make a paradigm shift (reform of flows, infrastructure, and needs) difficult. This stability can be perceived as harmful when confronted with third-order negative effects (negative externalities, transgression of planetary boundaries)13.

It may be tempting to ask whether a systemic reading of urban metabolism could have anticipated the long-term effects linked to the dismantling of certain infrastructures. However, such a hypothesis must be handled with caution. Urban planning choices — such as those that led to the removal and later reconstruction of the Bordeaux tramway — are not solely the result of functional optimization logics. They are also the product of specific historical contexts, political power relations, sectoral economic interests, and dominant representations of progress at a given time14. The current saturation of transport systems can therefore only be understood through this complexity, in which flows are but one element of the system.

Formalization of the FIN Model

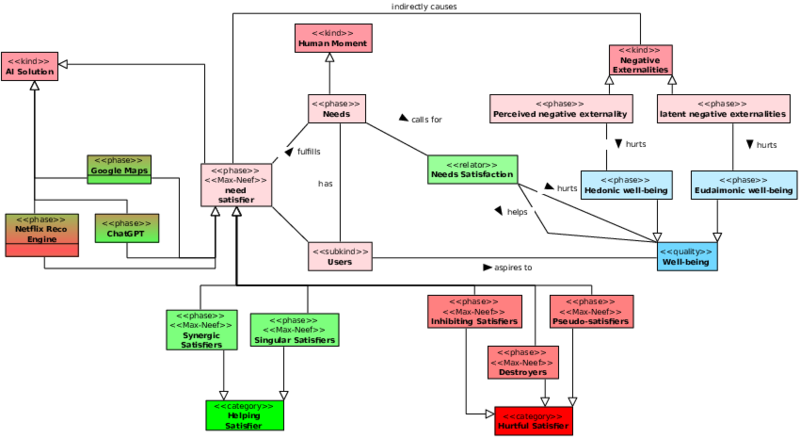

To describe the FIN model precisely, I adopted an approach based on the work of Guizzardi [Guizzardi 2005], relying in particular on the foundational ontology UFO (Unified Foundational Ontology). This ontological framework provides a rigorous modeling of entities, their relationships, and the ontological dependencies between them. It allows for an explicit representation, through a class diagram15, of the structural and dynamic concepts underlying the FIN model, while ensuring the semantic coherence of the whole.

The three main components of the system (Flows, Infrastructure, and Needs) are represented. There are two types of relationships between these components: first-order relationships (Infrastructure Building and Primary Infrastructure User) and second-order relationships (Infrastructure Maintenance and Induced Infrastructure Use). Flows have been divided in two to indicate their respective contribution to first- and second-order relationships. Similarly, Induced Needs, which are the co-products of the primary use of infrastructure, are the consequence of the first-order relationship between Needs and Infrastructure, and the cause of the second-order relationship between these two components.

Since needs are not acting entities, I introduce the entity Users, representing the infrastructure user. In this model, the User aspires to well-being, which can take two distinct forms: hedonic well-being16 and eudaimonic well-being17 [Lamb and Steinberger 2017]. I choose to consider that the needs driving the creation of infrastructures are led by the pursuit of hedonic well-being.

Flows and Infrastructures are agents exerting a direct systemic impact, unlike the user, who exerts an indirect impact through the use of infrastructure. These impacts produce third-order effects in the form of externalities. Externalities may be perceived, when the causal relationship between the impacting entity and the effect is directly perceptible by the user, or latent otherwise18. Perceived negative externalities impact hedonic well-being, in the sense that they directly affect it. Latent externalities, on the other hand, negatively affect well-being through its eudaimonic component19.

Within the application of this model using a complex systems approach, it is already relevant to identify the feedback loops that contribute to system stability:

- The Flows–Infrastructure loop is self-sustaining due to the necessity of maintaining existing Infrastructure.

- The Infrastructure–Needs loop is also self-sustaining, but modulated by the reduction of needs linked to perceived negative externalities.

- Latent negative externalities intervene only through their impact on eudaimonic well-being. They therefore do not exert a direct moderating effect on needs. A drastic reduction in eudaimonic well-being could lead to a degradation of overall well-being, which may be compensated for by intensifying the pursuit of individual benefits. Conversely, the hedonic motivations underlying needs may be weakened in the absence of an explicit quest for hedonic well-being.

- Finally, latent negative externalities are a limiting factor for impacting entities. In other words, these may be constrained if they exceed a certain threshold of sustainability.

The intuitive analysis of this system allows us to identify 3 stable states resulting from 3 scenarios20:

- degrowth scenario: suppression of the pursuit of hedonic well-being, which has the first-order effect of limiting infrastructures and, as a second-order effect, limiting flows.

- collapse scenario: the collapse of infrastructures and flows due to the overshooting of thresholds for latent negative externalities. This situation leads to a forced limitation of needs, as these can no longer be satisfied in the absence of infrastructure.

- controlled landing, awareness and limitation scenario: a limitation of flows and Infrastructure, reaching a level of latent negative externalities that does not sufficiently impact the pursuit of eudaimonic well-being to trigger a natural limitation of the pursuit of hedonic well-being, which would in turn limit needs. The existence of a stable state in this last scenario is not guaranteed, as it depends on physical laws, the initial state of the system, and the ability of stakeholders to become aware of and accept usage limitations reflecting the physical reality of resource constraints.

After detailing the model, I now propose to present my project of applying it to the metabolism of AI.

Application of the FIN Model to the Study of AI Metabolism

We will now analyze the metabolism of AI using the FIN model presented previously. Our objective is threefold:

First, I specialize the FIN model presented in the Figure by integrating elements specific to AI. It should be noted that the proposed elements represent an initial naïve approach, and the development of these models will need to be refined in future work. Then, I analyze the emerging dynamics specific to AI within the specialized model, in order to better understand its stability properties. Finally, I propose ideas for short- and medium-term scientific contributions aimed at enriching the model and suggesting solutions.

Les Flux

Dans ce document, nous simplifions le problème en ne considérant que les flux entrants, en ignorant les exutoires21 ainsi que les flux de transport des matières. D’autres flux entrants sont également ignorés pour nous concentrer sur deux grandes catégories: les flux matériels et les flux informationnels.

Les flux matériels proviennent des opérations de construction et de maintenance du matériel informatique nécessaire à l’exécution des tâches du cycle de vie de l’IA22. Dans le cas d’une IA centralisée (e.g., ChatGPT) et/ou mutualisée (e.g., Amazon Bedrock, AWS), la majeure partie des flux de construction d’infrastructure se concentrent dans les centres de données. De nombreux flux de matériaux sont nécessaires, comme les minerais métalliques ou les terres rares. Ces ressources sont non renouvelables à l’échelle de temps humaine, ce qui conduit à une raréfaction progressive. Selon le type de ressource et sa concentration dans l’environnement, cette raréfaction peut engendrer des effets négatifs différés : toute extraction non renouvelable se fait au détriment des besoins futurs. À titre d’exemple, aujourd’hui, le consommateur ne perçoit pas directement l’impact à long terme de la diminution du stock de cuivre. Selon l’élasticité des prix de la matière première, il pourra en percevoir l’externalité négative par une hausse des prix, sans que cela soit systématique.

D’autres flux sont potentiellement renouvelables. Les flux d’électricité ou de refroidissement peuvent l’être au premier ordre sous certaines conditions imposées à l’infrastructure de production, par exemple via l’usage d’hydroélectricité ou d’énergie éolienne23. Cette hypothèse ne tient toutefois plus au second ordre : les moyens de production de ces flux dépendent eux-mêmes d’infrastructures construites avec des flux non ou partiellement renouvelables24. Même en ignorant les effets de second ordre, un phénomène de compétition d’usage se manifeste : l’installation de centres de données limite l’accès à l’électricité pour les infrastructures voisines [Lopez and Diguet 2023], entrainant donc des externalités négatives.

Les flux de données sont essentiels à toutes les étapes du cycle de vie de l’IA : lors de la création des modèles, de leur utilisation, et pour leur maintenance en cas de model drift25, afin de préserver leur performance par réentraînement.

The data used can be public or private. Public data flows do not present particular negative effects at the first order. However, the performance targeted by models encounters two limits:

- personalized data are the most useful to users, but require the use of private data;

- an increase in public data flows may be necessary to improve model performance.

In either case, the use of private data proves necessary. The user must provide personal data if they wish for better model performance (e.g., in the case of personal assistants or recommendation engines). They may even be compelled to do so by public authorities26 or incentivized by private actors in exchange for access to their services27. Legislators nevertheless plan to strengthen user awareness regarding the use of their data, particularly through texts governing personal data protection (e.g., GDPR), which require obtaining their consent before any collection. This last observation allows us to classify the use of private data as a negative externality.

Infrastructures

The infrastructures mobilized by AI largely inherit from those already implemented for other uses:

Human resources: these include individuals trained in the use of AI tools, as well as professionals specialized in their design and maintenance. The case of users is particular, as many AI solutions rely on reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), where the very use of tools enables the expression of preferences regarding the outputs produced. This feedback is used to improve the models. It creates a dynamic of increasing returns to scale: the more the systems are used, the more effective they become for all users. Other human resources are dedicated to improving solutions: data workers28 contribute to the creation and quality of datasets, while AI engineers work on model optimization. The latter are highly qualified, requiring several years of academic training, which impacts their availability in the labor market and drives the creation of specialized training programs.

Informational infrastructure: this mainly includes the datasets used for training, the models used for inference, and a potential learning component. Other software components are close to those of traditional information systems and are ignored in a first approximation. All these elements rely on physical resources. While datasets can be stored with standardized big data technologies, learning components and models require specific hardware resources (GPU, TPU, NPU, fast memory), which are often not easily reusable outside the AI context.

Physical infrastructures: these include data centers, which today perform most large-scale training operations, the energy infrastructures required for their operation, and the devices enabling interaction with AI (mediation layer). The data entry points layer includes physical devices used to capture data to feed datasets. These may be consumer devices (personal devices) such as PCs or smartphones, or dedicated devices such as IoT sensors or medical equipment. Interface devices refer to the devices through which users interact with AI systems. They include both conventional devices (PCs, smartphones) and specialized devices with local inference or learning capabilities, such as virtual reality headsets or edge devices. Part of the AI lifecycle can thus be offloaded to the network edge to improve performance in terms of latency. The number of devices integrating AI capabilities is constantly increasing, with interfaces becoming more and more specialized for certain uses.

Regulation: AI is governed by specific regulations29 covering the entire lifecycle of systems, as well as more general regulations (privacy regulation, environmental regulation) impacting some of its components.

- Privacy regulations govern the use of personal data30.

- Environmental regulations impose constraints on the ecological footprint of physical infrastructures. This includes, for example, rules on soil artificialization by data centers (e.g., “zero net land take”), or rules limiting CO2 emissions31.

- Some of these rules are legally binding (binding regulations), while others fall under non-binding guiding principles.

The infrastructural subsystem of AI can be seen, in a first approximation, as a self-regulating system: some components consume resources (physical infrastructure), while others are designed to regulate this consumption and ensure compliance with the values of the host society (regulatory infrastructure)32. The system is also self-improving, in the sense that users contribute to the continuous improvement of models. With constant demand, it can thus become increasingly efficient.

However, as we have seen, the dynamics of infrastructure depend on human needs while also generating new ones. Its stability must therefore be analyzed systemically: second-order effects contribute to the continuous growth of infrastructural needs driven by system improvements. Furthermore, since models are subject to model drift, they must be maintained through the continuous addition of new data to datasets. A large part of the literature focuses on improving the environmental performance of AI, which is undoubtedly a progress for the field [Verdecchia et al. 2023]. Nevertheless, these considerations are no longer sufficient when studying metabolism to address challenges from a systemic perspective. Other researchers go further by considering both direct [Morand et al. 2024] and indirect [Wilson et al. 2024] impacts of infrastructures, producing results that are highly context-dependent and illustrate (1) the difficulty of identifying these phenomena and (2) the inherent methodological challenges.

Needs

Human beings have needs, in the sense of [Max-Neef et al. 1991]. These needs are met through Need Satisfiers, which can be grouped into two broad categories: Helping Satisfiers and Hurtful Satisfiers.

Several types of Satisfiers can be distinguished:

- Synergic Satisfiers: they effectively meet the targeted need while simultaneously contributing to the satisfaction of other needs.

- Singular Satisfiers: they meet a specific need without significantly influencing others.

- Inhibiting Satisfiers: they meet a need but hinder the satisfaction of other needs.

- Destroyers: they claim to meet a need but actually prevent its satisfaction, as well as the satisfaction of other needs.

- Pseudo-Satisfiers: they provide apparent short-term satisfaction but compromise the satisfaction of the need in the medium or long term. These are a particular form of Destroyers, whose negative effects are poorly perceived at the time of their implementation.

These Satisfiers can generate negative externalities that affect well-being while paradoxically constituting the very conditions of possibility for that well-being. Certain uses of AI can be easily classified. For example, the generation of deepfakes for deceptive purposes or cyberattacks targeting healthcare systems clearly fall under Destroyers. It is noteworthy that the Human Moment (the intention) is crucial in this classification, as it distinguishes intentionally malicious uses. Other uses of AI are not controversial: the AlphaFold solution, which enables the prediction of protein structures, or the use of AI for early detection of pathologies, represents major scientific advances in biology. Similarly, automated analysis of seismic data for earthquake forecasting directly contributes to population safety. Finally, some uses are more ambivalent. The use of ChatGPT by students can help them rephrase concepts covered in class, but it also facilitates cheating in project submissions, which compromises the acquisition of skills targeted by a degree. Netflix’s recommendation system offers personalized content but may also reduce cultural diversity in media consumption33. Helping Satisfiers contribute to eudaimonic well-being, while Hurtful Satisfiers may temporarily enhance hedonic well-being. However, each of these Satisfiers is likely to generate latent negative externalities and is not intrinsically sustainable. It is also important to note that many articles refer to AI as a possible solution to environmental problems, although the issue should not be addressed solely from the perspective of needs [Schoormann et al. 2023].

The needs subsystem thus allows for an initial classification regarding the sustainability of AI solutions, relative to the intentions of users, according to a first-order analysis. However, systemic sustainability also requires considering second- and third-order effects to fully assess the advisability of deploying such solutions.

Future Work

This section presents ongoing and upcoming work, which aims to contribute to the research field of AI metabolism studies, positioning my research within the framework of the FIN model described earlier. This framework opens the way to numerous scientific contributions, divided into four axes: first, a methodological axis to refine the model, followed by axes specifically targeting each of the FIN subsystems.

Methodological Axis: Refinement of the FIN Model

As mentioned earlier, many factors were left aside in our initial modeling. A more complete life cycle analysis, based on existing work [Bouza et al. 2023] and a systemic approach [Ekchajzer et al. 2024], would allow for a deeper understanding of the actual sustainability of the system. The difficulty, beyond data collection, lies in accounting for second- and third-order effects (rebound effects), which represent a real challenge for both researchers and public authorities [Courboulay 2023].

It would also be relevant to examine the causes of the current transformation toward a society increasingly dependent on AI. The mere availability of technical capacities resulting from innovation is not sufficient to explain such a shift. This dynamic rather seems to be embedded in deeper societal transformations — economic, cultural, and political — which reshape representations of progress, efficiency, and well-being34.

Needs Axis: Adoption of AI — the Double Role of Trust

Trust, understood as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party” [Mayer et al. 1995], plays a central role in the adoption of artificial intelligence solutions.

However, the study of trust as applied to technical systems adapts poorly to systems based on AI. While certain classical dimensions remain relevant — such as performance or transparency — the anthropomorphic characteristics of AI systems tend to blur the traditional reference points of trust analysis [Lankton et al. 2015].

From this observation, we have undertaken research on trust mechanisms in AI systems, not with the aim of promoting or strengthening user trust, but rather to identify the factors that generate it, their interactions, and the conditions under which legitimate trust emerges35.

This distinction is essential in the framework of needs classification. Indeed, Max-Neef identifies Pseudo-Satisfiers as solutions imposed on individuals through propaganda or advertising, which ultimately prevent the authentic satisfaction of their needs. Restoring trust in AI to its proper place thus allows us to better qualify legitimate uses serving human needs, independently of the question of their material sustainability.

Infrastructure and Flow Axis: Feasibility and Evaluation of Decentralized AI Solutions

As illustrated by the application of the FIN model, the deployment of the centralized AI model we currently know raises problems in terms of flows and infrastructures. We have also begun to study the substitutability of this model in the case of home assistants36. These — just like, on a larger scale, the concept of the smart building — show, at first glance, energy efficiency gains and reduced maintenance costs [Ejidike and Mewomo 2023], though these must be balanced against the environmental impact of large-scale deployment of such solutions.

We are exploring the possibility that a disconnected, explainable, and coachable model could address the challenges posed by the unsustainability of flows, respect for privacy, and the limitations of current infrastructures.

We are currently developing an edge device prototype37 to address these challenges while maintaining a high level of service and user acceptance [Vrain and Wilson 2024].

Decentralization also involves adopting solutions that enable users to reclaim control over their data, without excluding third-party uses if deemed necessary. The study of blockchain-based solutions developed in the context of self-sovereign identity [Preukschat and Reed 2021] is one path that could enable fine-grained control of these data and their use in AI systems, once again subject to a sustainability assessment.

Limits Axis: Exceeding Planetary and Cognitive Boundaries

While IPCC reports leave no doubt about the transgression of planetary boundaries, another threat linked to the deployment of AI solutions lies in exceeding human cognitive boundaries. Indeed, performance — rather than explainability — is currently the main objective of the promoters of these technologies.

The fear is that development may reach a point where humans are no longer able to understand or interpret the results produced by models that have become indispensable to the functioning of our societies.

It is therefore essential to study in more detail the human cognitive limits to be respected, as well as the technical means to ensure that AI systems account for them.

Conclusion

This document establishes the conceptual and methodological foundations of my future work on the metabolism of artificial intelligence, based on a foundational approach formalized through the FIN model. By articulating flows, infrastructures, and needs, this framework makes it possible to analyze the stability and sustainability of sociotechnical systems integrating AI.

The application of this model to ubiquitous AI reveals complex dynamics, where apparent gains in performance or comfort are often accompanied by negative externalities, structural lock-ins, and systemic rebound effects. Taking into account human, regulatory, and material dimensions, as well as second- and third-order effects, appears essential to understand current trajectories and to consider sustainable alternatives.

The proposed research axes open the way to interdisciplinary contributions aimed at exploring technological and organizational alternatives — notably through decentralization, explainability, and the redefinition of legitimate uses of AI with respect to human needs. The work initiated here constitutes a first step toward a systemic understanding of the social and ecological footprint of AI, and toward the development of landing scenarios compatible with planetary and human boundaries.

References

Blockchain, socio-technical aspects: see the theses of Nicolas Six (2019–2023) and Claudia Négri (2019–2023). ↩

Trust and AI: see the theses of Eddy Kiomba (2022–2025) and Yuntian Ding (2024–2027). ↩

In this document, I use slightly different terminology — Flows-Infrastructure-Needs (FIN) — as it more clearly reflects the materialities of the concepts at play. ↩

Deloitte forecasts an increase in electricity consumption linked to AI from 1680 TWh to 3550 TWh per year by 2050. ↩

https://s.nextnet.top/tram “Le tramway de Bordeaux, une histoire,” Christophe Dabitch, Editions Sud Ouest. ↩

car fuel, consumables, transported goods… ↩

the new road infrastructures built in Bordeaux to replace the tram: cars, roadways, parking lots, gas stations… ↩

Needs are the individual benefits expected from the establishment of infrastructure: additional freedom of movement, improved comfort, and time savings. ↩

the increase in the number of available roads increases the number of cars and their uses. ↩

the use of individual cars allows time savings in commuting, which encourages residents to live further from the city center in areas newly accessible thanks to cars, leading to increased use. ↩

In the case of Bordeaux’s tram, this was facilitated by the deterioration of the network after the war, leading to an exogenous reduction of infrastructure. ↩

For our example, the post-war context gave priority to reconstruction, which facilitated the acceptance of the removal of the electric tram and its replacement by the more modern diesel bus, again exogenously. ↩

The previous state of the system (1900–1946 period) was overcome only through two exogenous effects: the deterioration of infrastructure due to the Second World War, and the automobile culture, erected as a symbol of progress after the Liberation, combined with intervention by the central state through the Commissariat for Reconstruction. ↩

Several other factors have been put forward to explain the lack of maintenance of the historical network. Among them: aesthetic constraints leading to the adoption of unreliable APS systems, the repelling effect felt by bourgeois classes due to the easy access of working classes to the city center, the absence of lobbying for the maintenance of existing infrastructures, and the progressive disengagement of the State [Turnheim 2023]. ↩

https://ontouml.org/ ↩

Hedonic: Related to immediate pleasure, the hedonic approach to well-being evaluates an individual’s experience based on the positive and negative affects they feel, as well as the satisfaction of their desires or preferences. ↩

Eudaimonic: The eudaimonic approach to well-being focuses on self-realization, life meaning, and the actualization of personal potential, beyond mere pleasure or momentary satisfaction. ↩

for example, traffic jams on the ring road are a perceived negative externality, while the disappearance of an amphibian species during highway construction is latent. ↩

the phenomenon of eco-anxiety is the most direct manifestation of latent externalities: affected individuals suffer from a lack of prospects for the future and for future generations, without necessarily perceiving immediate effects [Stanley et al. 2021]. ↩

the scenario-based approach is inspired by [Meadows et al. 2018]. Even if degrowth and collapse scenarios are rarely addressed in computer science research [Bugeau and Ligozat 2023], we believe it is relevant to present them in our conceptual framework. ↩

many studies on the life cycle of computing devices and e-waste management have been published, showing the problem and the limits of solutions [Kiddee et al. 2013]. ↩

AI lifecycle: data collection, preparation, feature extraction, training, testing, and inference. ↩

AI and Renewable Energy: given the sometimes intermittent nature of renewables and their share in installed power, this condition is not met today, even though many cloud providers purchase renewable energy certificates and invest in renewables (e.g. https://s.nextnet.top/clean_apple). ↩

60% of the weight of a wind turbine consists of concrete, which cannot be recycled in a closed loop, only downcycled as aggregate. ↩

Model drift results from the growing disparity between the data used to train the model and the data currently available. In the case of LLMs, this phenomenon can contribute to misinformation [Fastowski and Kasneci 2024]. ↩

For example, the temporary authorization of automatic facial recognition during the Paris 2024 Olympics, whose extension beyond 31/03/25 is requested by the Paris police prefecture https://s.42l.fr/JTRs_YJd. ↩

For example, the use of private data by Google in exchange for the Gmail service [Newman 2013]. ↩

Chinese “Data Annotators” play a crucial role in the success of DeepSeek, but their subsistence conditions raise ethical concerns [Casilli et al. 2025]. ↩

the European AI Act is one example. ↩

for example GDPR in Europe, CPRA in California, or PIPL in China, with different scopes and sometimes privileged access rights for public authorities (PIPL). ↩

the “European Green Deal” is one example. ↩

Even though the relevance of regulators’ decisions regarding the sustainability of ICT infrastructure is debated [Mollen et al. 2024]. ↩

See my participation in the Paris 1 Chair: Cultural Pluralism and Digital Ethics, where we studied the impact of recommendation engines on European audiovisual production. ↩

Eric Sadin even suggests the establishment of a new civilizational model, stripping human beings of their free will in favor of algorithms [Sadin 2016]. ↩

Recent updates to ChatGPT have made it highly anthropomorphic, creating unprecedented confusion regarding the level of trust the public may grant it. ↩

Home assistants such as Alexa or Google Home are based on centralized AI in GAFAM data centers. The project CUPID25 aims to propose an alternative and evaluate its sustainability. ↩

We have started working with the Raspberry Pi 5 platform and the Hailo-8 AI accelerator, which drastically reduces energy consumption linked to inference. ↩